letter 002 - the confessional poets department

on 'confessional poetry', writing from what you know, creative imposter syndrome, and singer-songwriters

My brother and I love to talk about art. From music to movies and books, our conversations range from entirely unserious to deeply consequential, and tend to explore where we aspire to most. A few months back, our chat dove into his uneasiness with the blunt lyricism found in so-called confessional songwriters. As he explained, I felt a tiny fuel of fear ignite in my belly. Is that what I’m becoming? Is that who I already am? Confessional? I have never intended to be, and yet, to some extent at least, I think I am.

To sit here and write about this experience alone, I assume an autobiographical style of writing. Analyzing this mini epiphany inspired an artistic crisis of sorts. And while I know my brother was good-natured in his simple critique, what he said did impact my own understanding of what it means to consume and create art.

I tend to like songs, poems, and books that reference specific places and things. I like for instance, to get a clear picture of the café the artist references, the way the rain fell on the window pane. I want to delicately analyze the person the art is about. As vague as the details offered may be, I like to paint a picture.

This is somewhat in opposition to my brother. While I tend to spend my days listening to Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers, he prefers the more abstract lyricism of artists like Pavement or Soft Machine. In fact, he admittedly doesn’t spend much time thinking about lyricism at all. This isn’t to say that we don’t each admire the works and styles of the other’s favourite, however our overarching differing tastes naturally reflect the ways in which we understand art and conduct it.

It is natural to take inspiration from real life, and nearly impossible to write without any personal bias whatsoever. A variety of deeply unique factors intertwine in order to shape the ways in which we think about the tiniest parts of creating and sharing art. They impact miniscule details, from the colours that resonate with us or our desired word choice. And while it is possible to avoid bias, it is impossible to eliminate it entirely.

In some spaces, this idea may be received more positively than in others. Different people, and even professions at large require differing percentages of bias. A person that performs objective research for instance, may not have the same flexibility to play with detail that an opinion columnist may have.

In a Vanity Fair interview from 2017, Judd Apatow, Shonda Rhimes, Jonathan Nolan, and Lisa Joy were asked to talk about the truths and myths of writing and filmmaking. One of the parts of the interview I find most intriguing is when Lisa Joy, co-creator, and executive producer on Westworld discusses the notion of writing from what you know. She states, “The write what you know adage has done real harm sometimes to women in the industry. A lot of these executives are men and they’re like I don’t know what women know … but it’s definitely not this multi-million-dollar franchise, and to that I say, ‘I know that, I know how to do that’, so you know let’s write that too.” In the same interview, Shonda Rhimes, creator and executive producer of Grey’s Anatomy and Scandal (among other things) takes a similar stance, “I definitely wrote what I didn’t know when I wrote a show about surgeons because I don’t know anything about surgery and blood makes me queasy. I think it’s more fun to write what you don’t know.”

While these notions may be accurate and helpful reminders so as not to box oneself in entirely within the realm of creative writing, they do not mean that writing from what you know is an inherently negative thing. Many writers, specifically within the disciplines of music and poetry lean heavily upon their personal experience to develop narratives. Just as is the case for many, writing is a way to process emotions and feelings. If this is the case, what leads one to be labelled autobiographical or confessional? The difference can be found in the phrase’s origins.

The term “confessional poetry” comes from critic M.L. Rosenthal’s review of Life Studies by Robert Lowell back in 1959. In his poems, Lowell discusses issues ranging from distress in his marriage to his battles with mental illness. And while these topics have always been somewhat common within the realm of poetry, Rosenthal critiques the work of being a “series of personal confidences, rather shameful, that one is honor-bound not to reveal.”

In spite of its origins referring to Lowell, the term confessional poetry has since become more closely associated with female artists in poetry or musical spaces, specifically those who tend to discuss the politics of gender or topics that are considered taboo within the realm of womanhood.

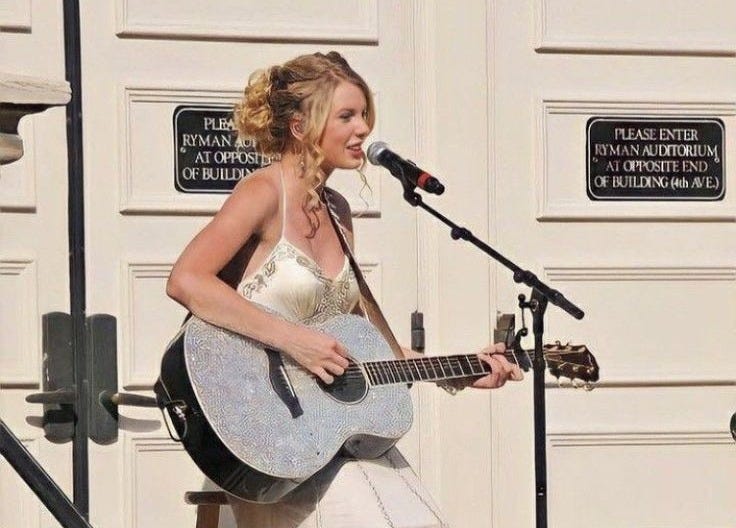

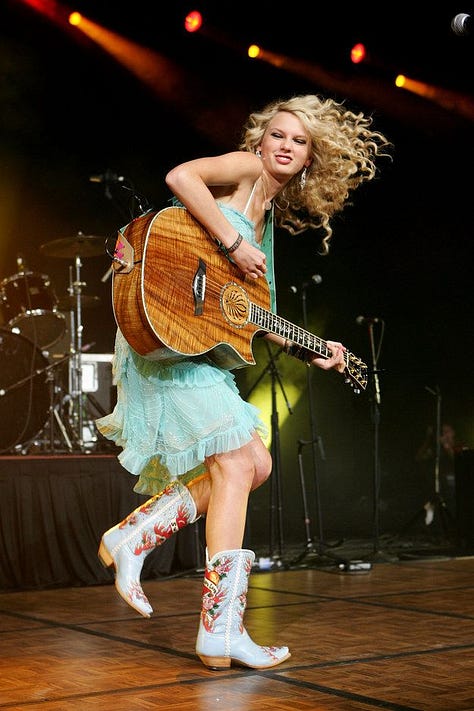

In particular female singer-songwriters often seem to find themselves inescapably attached to the label of confessional. One of the most popular modern examples of such is seen in Taylor Swift. Since early in her public prominence, Taylor and her song writing have been adored and critiqued for their autobiographical nature. Her discography approaches a variety of very personal aspects of her life, from mortality and illness to depression, revenge, regret, and longing.

For Swift, writing in a deeply personal, almost testimonial nature has been both her way of contributing to and controlling the narratives the media has spun about her. Though she rarely comments directly on who or what her songs are about, she often uses easter eggs and clues that connect her love life and feuds to various songs and albums. This especially is something that has led to critique. Back in 2010, Sady Doyle wrote of Swift in The Atlantic stating that “[l]ike it or not, Taylor Swift is apparently the confessional female singer/songwriter of her generation.” Doyle’s use of the term “confessional” is not one of praise or appreciation in the context of her article, but rather, a slander. Such a review echos those directed towards confessional poets of the past, from Sylvia Plath to Anne Sexton. They seek to undermine the art of the poet in question, diminishing their artistic contributions to that of an “immature” diary entry. As such, the use of the word confessional in and of itself is often interpreted as a clever back-handed compliment.

When Joni Mitchell, largely vocal about her discontent for the label, was asked to explain her feelings towards being classified as confessional she stated,

“When I think of confession, two things come to mind. The swinging light and the billy club – trying to get a confession out of somebody that’s been captured. Confess, confess! Or a witch hunt. Or trials. Confession is somebody trying to beat something out of you externally. You’re imprisoned. You’re captured. They’re trying to get you to admit something. To humiliate and degrade yourself and put yourself in a bad position.” She continued: “Then there’s the voluntary confession of Catholicism, where you go to this window and you talk to this priest and tell him that you’re having sexual fantasies and he’s wanking on the other side of the window. That’s the only two kinds of confession I know – voluntary and under duress – and I am not confessing.”

Here, Mitchell brings up an important concern. Why is it that a term so deeply associated with guilt and shame is used so often to describe the way women artistically explore political or personal themes that men dabble in just as frequently? Turning the personal to political and the relationship between being labelled autobiographical or confessional is a fine line, but gender’s intersection with it is undeniable.

Another singer-songwriter long-criticized for her overtly personal references is Canadian Alt-Rockstar Alanis Morissette. Throughout her years in the musical industry Morissette has referenced everything from loneliness, anger, and trauma in her songs. She describes parts of her own work as “hyper-autobiographical” but this is in no means a discredit to her own talent or choice of subject matter. Rather, Alanis aims to reclaim her story, take the frequent patronization, and cast it aside in order to unapologetically approach the more messy or uncomfortable aspects of the female experience.

Following in the footsteps of Alanis Morissette, is Olivia Rodrigo, a prime example of a modern female artist refusing to allow herself to be boxed in by the label of confessional, even when the topics she often chooses to engage with are deeply personal. Rodrigo has been extremely intentional and clear in her interviews that she does not wish to so much as hint at who or what her more personal songs are about. When asked about potential reference to a feud with Taylor Swift in an interview with The Guardian, Rodrigo stated:

“I mean, I never want to say who any of my songs are about. I’ve never done that before in my career and probably won’t. I think it’s better to not pigeonhole a song to being about this one thing.”

Her hesitation could be a result of the dramatic love triangle debacle that unleashed upon her introduction to the musical scene, or it could be an absorption of the techniques of those who have come before her, a form of protection. Either way, the sentiment alone is undoubtedly encouraging.

An artist never needs to explain their art. Even Taylor Swift, who has made a career, amassed an insanely large following, and quite literally made billions of dollars off of her confessional image, does not ever owe the public an all-encompassing picture of her personal inner life. This however does not mean that art should never reflect one’s personal experiences and lessons either. In fact, I firmly believe that all art is personal. And if its exploration of the personal is blunt and finger pointing, why shouldn’t it be?

I often find myself thinking of the scene (depicted below) from Steven Spielberg’s semi-autobiographical movie The Fabelmans, in which he depicts Sammy Fabelman (the fictionalized version of himself) filming a traumatic moment in his teenage-hood. I feel this scene is such a beautiful way of exploring how closely connected art is to processing trauma and healing from it. It shows that an artist’s personal experiences find themselves intertwined with their art so naturally, even if it may come across as intently blatant.

Maybe it isn’t trivial to approach creativity through a directly personal lens, perhaps it is a bold way to reclaim the notion of unabashed truth, owning one’s narrative, a way to learn and grow and share with others so they may learn and grow as well. For so long, artists, particularly those who are women, queer, or people of colour have fought to reclaim a space for their stories. Perhaps there is nothing wrong with finding a place within such an intentionally crafted space.